29th January 2018

A night with Police Scotland

Lucy McDonald is SafeLives’ Programme Lead for Scotland. In November 2017, as part of the 16 Days of Action campaign, Lucy accompanied Police Scotland on a night shift to see first-hand their response to domestic abuse.

On a cold November night, when I would usually be enjoying the comforts of home, I found myself in the back of a police van, along with fellow domestic abuse specialists from ASSIST and Hemat Gryffe. As part of Police Scotland’s 16 Days of Action to end violence against women and girls campaign, we were invited by Detective Superintendent Gordon McCreadie, Police Scotland’s national lead on domestic abuse, to do a night shift to give us an insight into how the police respond to domestic abuse.

First stop was a tour of the Contact, Command and Control Centre in Glasgow, one of several such centres in Scotland which takes 101 and 999 calls made to police. Led by a white-ribbon wearing Chief Inspector host, we were taken firstly to the Service Centre where the calls come in. A bustling room, we immediately got a sense of the sheer scale of the task at hand. It was 7pm, a quick check on a screen told us that since midnight there had been almost 3750 101 calls, 800+ 999 calls and almost 200 other emergency calls. We asked, of course, about domestic abuse calls and were told that in a 24 hour period the previous weekend, there had been 187 calls and that on an average day they received 161.

Under the old regional systems, prior to the formation of a virtualised Service Centre, there were a finite number of telephone lines into each individual Service Centre. This meant that a single incident, such as a road traffic accident on one of Scotland’s busy motorways might attract dozens of calls from the public tying up the limited phone lines whilst other parts of the country were quiet and had capacity. So, if you were a victim of domestic abuse needing urgent assistance at the same time, there was a chance your call might not get through because of the peak in demand. Now, with the National Virtual Service Centre approach there is much greater capacity to handle calls from across Scotland so callers are more likely to get the right response first time. We found out that almost all 999 calls are answered in less than 10 seconds, most far quicker, and the majority of non-emergency 101 calls were being answered within 40 seconds.

We were quickly directed over to a Service Advisor who was taking a call from a woman reporting domestic abuse. The sophisticated system showed immediately that the woman had called earlier in the night, but the emerging picture was now becoming concerning and the handler upgraded the call to a Priority 1, which meant a response team would be dispatched immediately. In the Area Control Room next door, we were shown the process of dispatch, watching in awe as a police officer skilfully worked her way around a complex system using electronic mapping to identify the closest, most appropriate officers in one sub-division to multiple jobs based on location and competing priority levels.

Now 9pm, it was time to see things on the ground so we piled back into the van for the short drive over to one of the police hubs in Paisley, just in time for the start of a new shift. We got a briefing from the Inspector overseeing the shift, who explained their approach to domestic incidents and their determination to keep the quality of response high at all times. He admitted this was challenging at times, mentioning a home nearby where there had been 128 police call outs. 128. A chronic cycle of a woman being subjected to ongoing physical violence and coercive control, periods of separation and reconciliation, amongst other criminality and alcohol abuse. The challenge, he said, was to ensure that his team never became desensitised to the risk of harm to that woman.

Back out in the van, as we took to the streets and admired the pretty Christmas lights in the town centre, my mind kept returning to the woman who had called the police 128 times. Was she looking forward to Christmas? Was she full of hope, or full of fear and despair? I could guess the answer.

As the night got colder and the streets got icier we listened to the airwaves, which were unexpectedly quiet. There was some activity about a possible missing person, but that died down. We wondered if everyone was at home, keeping cosy.

And then a report came in. It turned out to be the 129th call of the woman I’d been wondering about. Her ex-partner had been released from custody earlier in the week and she thought she’d heard someone rattle her letter box. As we turned the van and started to make our way to the address the Inspector told us they’d had a similar call from her earlier in the week and it had turned out to be neighbours. A woman on high alert, I thought, waiting for the next incident. I pondered the kind of response she would get tonight from the cops who’d been dispatched - were they thinking ‘here we go again…’? When we reached her street, the answer was obvious. The patrol car was already there and the officers were making their way into her house. We waited anxiously in the van across the street. Then we heard an update and request on the radio – there was no sign of her ex-partner in the building but could a check be made of street CCTV footage from the last hour to assure the officers on movements in the area? Fortunately this came back negative. Twenty minutes later the cops emerged having offered reassurance to the woman that they have become so familiar with, the woman living in a heightened state of anxiety and coping the only way she can.

Shortly after this, we called it a night after what had been an insightful experience with fellow police and domestic abuse colleagues. And as I drove back to the warmth and comfort of my home, I reflected on the events of the night. I was aware that domestic abuse accounted for at least 20% of police business (over 58,000 incidents recorded in 2016/17), but seeing the stark reality of call volume first-hand really hits home the scale of the problem.

I already knew that victims of domestic abuse will be subjected to physical and emotional abuse for years before getting the right support. Indeed, in Whole Lives we found that people experiencing the highest levels of domestic abuse in Scotland will wait an average of four years before accessing or being directed to the right form of expert intervention. What I saw first-hand that night was Police Scotland doing the best they can to respond and reassure, make the appropriate referrals, apprehend perpetrators when they can. They did what they could to support the woman who called them so regularly, and there was much I didn’t know about her circumstances: was she in engaged with local domestic abuse services, did she have an Idaa1 supporting her, had she been referred to Marac2, or was her partner at MATAC3?

In the last decade we’ve seen major changes in the response towards victims of domestic abuse and how perpetrators are managed, by Police Scotland and other key organisations. We continue to see changes and progression, such as the anticipated Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Bill which will create new offences around coercive and controlling behaviour. However, alongside these improved processes and systems, the most effective response requires partnerships between both statutory and voluntary services, and an approach that combines belief and validation for the victims’ experience alongside practical and tailored intervention led by the victim and tailored to their needs and risk. This also means being creative about what we can offer to everyone experiencing domestic abuse, regardless of who they are, their circumstances and whether or not they have been able to leave the relationship.

And we need this in a way that is consistent across every part of Scotland. Granted, there are great examples of this in locations across Scotland, but at the moment it very much depends on where you live, what is available to you there and which services are working together. That is what needs to change, and only through positive collaboration can we make this happen, only together can we improve the wellbeing and safety of families experiencing domestic abuse across the country, reduce the volume of those experiencing domestic abuse and the time it’s taking them to receive effective intervention.

Thank you Police Scotland for inviting us into your world.

About Lucy McDonald

With a background in psychology, Lucy began supporting children affected by domestic abuse, before moving into refuge and then settling into domestic abuse advocacy. She began working with SafeLives in 2006, supporting the development and delivery of numerous training and accreditation activities across the UK including Idva, Marac and Leading Lights. Most recently she has been heavily involved in implementing the Idaa training programme, as well as programmes for Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, Police Scotland, NHS Health Scotland, the Caledonian System and a variety of teams and services across Scotland. Her expertise is in safe and effective responses to domestic abuse including risk identification, multi-agency collaboration and whole-family safety planning.

1Independent Domestic Abuse Advocate

2Multi Agency Risk Assessment Conference

3Multi Agency Tasking and Coordinating

Royal Infirmary (there is a Bank Idva to cover any outstanding shifts). She leads me to the A&E department, and to the Idsva service’s cosy little office which is a stone’s throw from both A&E and the staff room.

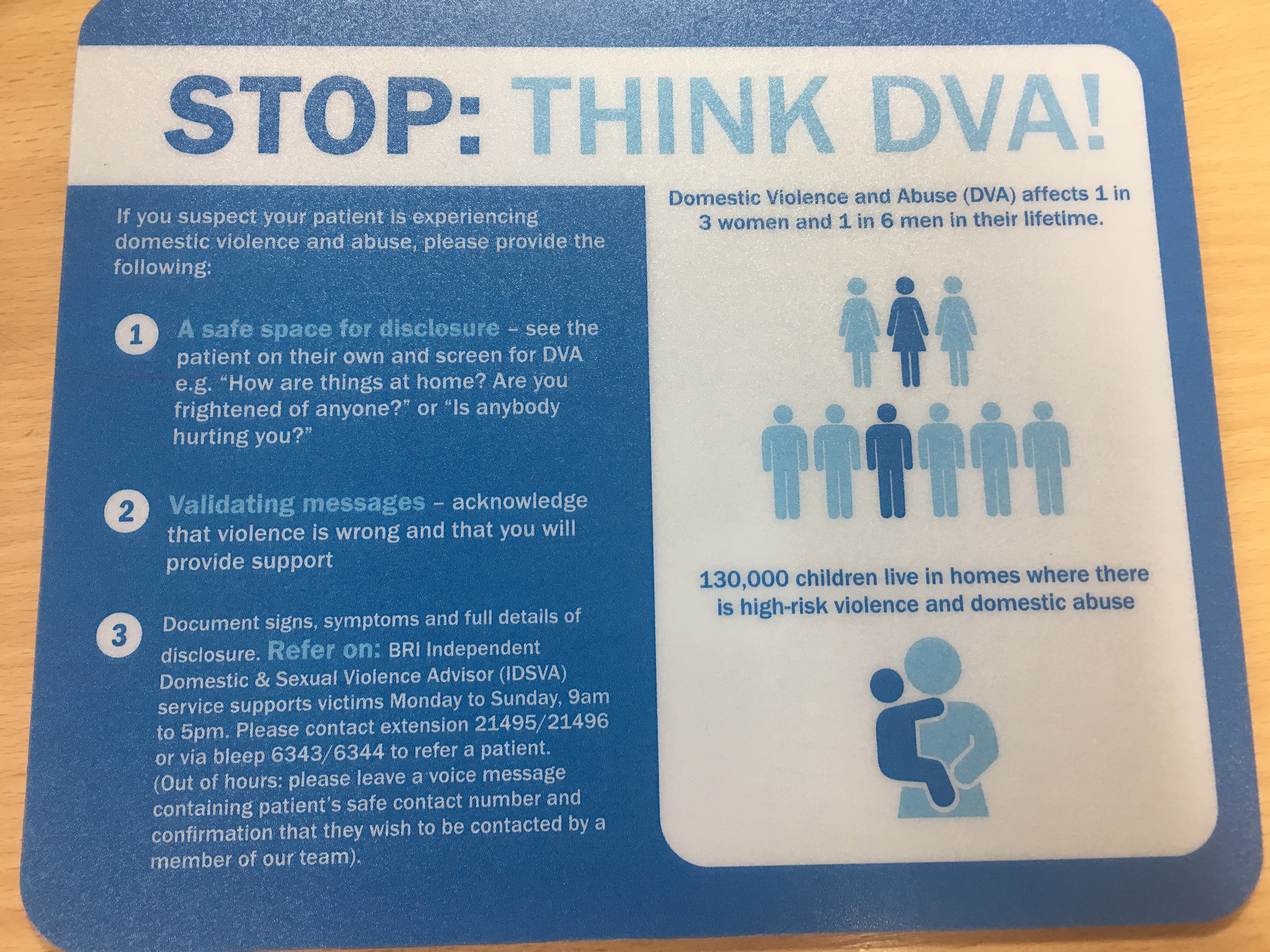

Royal Infirmary (there is a Bank Idva to cover any outstanding shifts). She leads me to the A&E department, and to the Idsva service’s cosy little office which is a stone’s throw from both A&E and the staff room. Punita and I take a walk around A&E, which she does every day. She shows me the cubicles where patients are seen by clinical staff – Punita has made sure that these cubicles have posters on the walls, highlighting the signs of abuse and mouse mats at every work station, in case a new member of staff needs guidance on how to “Ask the question” and refer on. “We have a high turnover of junior doctors, so the mouse mats play a key role in getting this information out”.

Punita and I take a walk around A&E, which she does every day. She shows me the cubicles where patients are seen by clinical staff – Punita has made sure that these cubicles have posters on the walls, highlighting the signs of abuse and mouse mats at every work station, in case a new member of staff needs guidance on how to “Ask the question” and refer on. “We have a high turnover of junior doctors, so the mouse mats play a key role in getting this information out”.