31st May 2017

'Honour'-based violence and risk

Dr Lis Bates researches gender-based violence at the University of Bristol. She is currently working on a project developing what justice means to victims of domestic and sexual abuse, and a European project to address sexual violence amongst refugees.

Lis’s interest lies in connecting research to policy and practice. Prior to 2016, she worked as Head of Research for SafeLives and, before that, for parliamentary select committees on Home Affairs and Education, running national inquiries on domestic abuse, immigration, crime and child welfare. Between 2010 and 2017 she completed her PhD study on ‘honour’-based abuse and forced marriage in England and Wales, analysing 1,500 cases known to the police and domestic abuse agencies.

Why risk assessment?

Perhaps the most famous case of ‘honour’-based violence (HBV) in this country remains the 2008 murder of Banaz Mahmood. And that’s because Banaz’s case really stirred things up. It drove the police to overhaul their response and write the first national HBV policing policy. The major failing in the police response to Banaz’s request for help was that they did not understand the context and therefore the risk signs of HBV. Consequently, they thought that her assessment of the threat to her own life was “hysterical” and unfounded. Her brutal murder a few days later showed just how misguided this was.

A key aim of risk assessment is to identify the contexts of abuse and help understand the threats to the victim. It enables professionals to help the victim safety-plan, manage risks and access the right interventions. Risk tools such as the 24-question DASH-RIC (used by police and domestic abuse services in England and Wales) draw on research from previous cases, and what victims say, to develop a checklist of questions professionals can ask to assess risk.

More HBV cases are high risk

HBV is much less prevalent than domestic abuse, but there are still a sizeable number of cases in this country each year. Annually, around 1,800 incidents are reported to the police in England and Wales (HMIC, 2015).[1] Of course, these numbers are just what are visible – the tip of the iceberg.

SafeLives Insights data published as part of the current Spotlight on 'honour'-based violence and forced marriage shows that HBV cases were more likely to score high-risk (68%) than non-HBV domestic abuse cases (55%).

Some HBV cases score more highly than others

The dynamics and risk factors for domestic abuse are quite well understood. However, little research has been done on large sets of cases to identify risk factors for HBV. My PhD research (as yet unpublished) addressed this gap, looking at almost 1,500 cases of HBV identified by the police and domestic abuse services in this country.

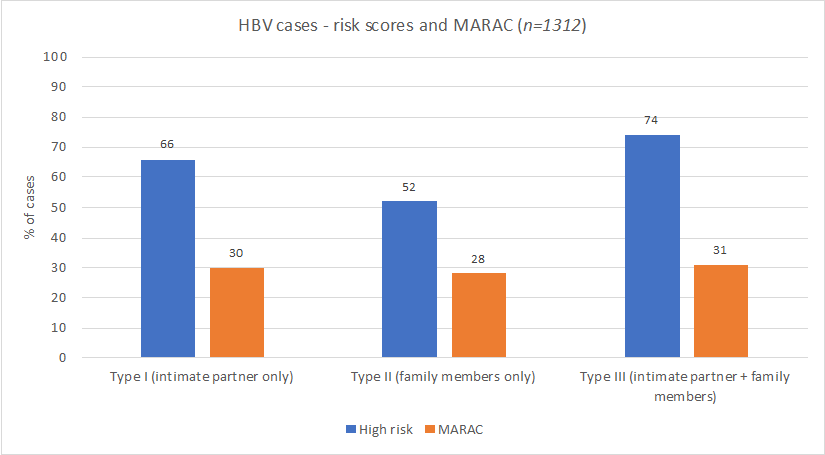

My study developed a new ‘typology of HBV’, with three types based on the relationship between victim and perpetrator, and number of perpetrators. In Type I the sole perpetrator was a current or ex intimate partner (very similar – arguably identical – to other domestic abuse cases). In Type II the perpetrator was one or more of the victim’s family members, generally their birth family. Type III involved a current or ex intimate partner perpetrator, and in addition one or more of the victim’s family members – most commonly their in-laws.

When cases were divided into these types, risk diverged. Type II scored lower, with only 52% high risk (as measured by Insights data), compared with 66% in Type I and 74% in Type III. This correlation between risk and type was statistically significant. Despite this, all three types were equally likely (around 30% of cases) to go to Marac. See figure below.

The key difference was that cases which did not involve an intimate partner perpetrator (Type II) scored lower risk, but went to Marac at the same rate. This is intriguing, on both counts.

So what?

What might be going on here?

Are the risks posed by family members (compared with intimate partners) less visible, or their dynamics less understood – and so these cases under-scored on risk? It could be that tools like the DASH-RIC, initially developed from analysis of intimate partner violence, are less well-equipped to identify risks from family perpetrators. For example, items on child contact, separation, pregnancy, or prior criminal history may be less relevant in familial HBV cases, and thus the sum total number of ‘yeses’ fewer. It is true that family member perpetrators can be an ‘unknown quantity’ in terms of risk, since (unlike many intimate partner perpetrators) they often do not have a prior police record and therefore it is harder to draw on past behaviour to judge the risk they pose. Some HBV cases also have characteristics which might lead to them being judged lower risk. For example, in my Type II, a female perpetrator (often the victim’s mother) was more likely to be involved (alongside a male relative). Is it possible that professionals scored cases involving a female as less risky (perhaps because a mother can traditionally be seen as a protective factor)?

If this picture is true, some items on risk assessment tools may need revisiting, especially for familial HBV – but professionals may be right to elevate these cases to Marac.

On the other hand, perhaps risks posed by family members can be less than those from an intimate partner. In some cases, family members can be protective as well as risk factors – and these cases usually lack certain elements such as sexual violence or the victim having children. If so, some Type II cases may be mistakenly elevated to Marac unnecessarily, perhaps reflecting local policies – such as referring all HBV cases – which operate in some areas.

These new figures and understandings about different types of HBV case – and the questions they pose about risk factors – are just the start of a much-needed conversation. But that conversation is timely, in light of this SafeLives Spotlight, and the current review of the DASH-RIC. I would love to hear the thoughts of front-line professionals, of HBV campaigners, Marac chairs and so on. What do you think these case types mean for risk, and for policy and practice responses?

Lis can be contacted at lis.bates@bristol.ac.uk.

Visit our Spotlight homepage for more insight and guidance for professionals encountering 'honour'-based violence

[1] In the ten months to 31 January 2015, a total of 2,600 incidents of HBV, forced marriage and FGM were recorded by 41 out of 43 forces in England and Wales. To make the figures comparable to other annual reports, if these data for ten months were uprated to 12 months (using a simple multiplying factor of 1.2), the annual number of incidents would be 3,120 incidents. 60% of these were HBV (the rest were forced marriage or FGM) – this would equate to 1,800 incidents. HMIC (2015) The depths of dishonour: Hidden voices and shameful crimes. An inspection of the police response to honour-based violence, forced marriage and female genital mutilation. Available at: http://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmic