Seeing the whole picture

At SafeLives, our mission is to end domestic abuse, for everyone and for good. We take a holistic, public health approach to ending domestic abuse.

To end domestic abuse, we need to look at the whole picture.

This means:

- Seeing and responding to the whole person, understanding linked adverse experiences and individual characteristics and situation.

- Wrapping around all family members involved, so the responses provided are coordinated and sustainable.

- Ensuring appropriate roles are taken on by the community, and society as a whole.

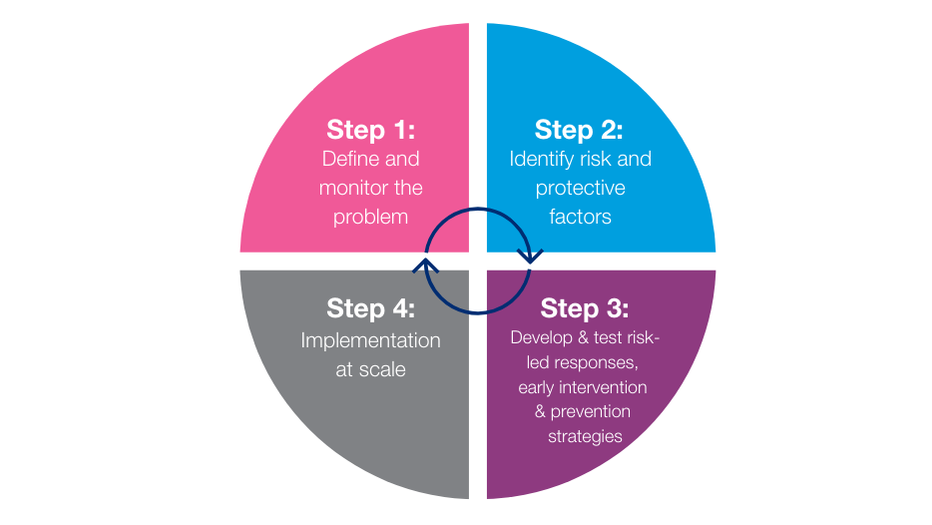

Acting at each opportunity for change and intervention, from before harm happens to after the most imminently dangerous moments have passed and people are trying to rebuild. - SafeLives works with local strategic and operational leaders, and frontline practitioners in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. We bring together data, practice expertise and survivor voice in a public health approach, based on the four steps endorsed by the World Health Organisation.